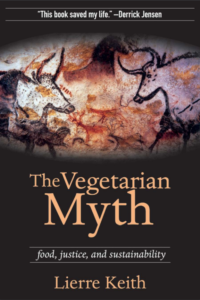

The Vegetarian Myth

“Elder, Today, a sesión wiser

And fainter, too, as Wiseness is”

Emily Dickinson

I heard about the book The Vegetarian Myth a few months ago, and as a professional in the restaurant world I read it and was really surprised, as it was rigorous and honest. That was a while ago, but today I would like to discuss some of the ideas I thought most useful and share them with you.

The Vegetarian Myth

It is written by Lierre Keith, who was a vegan for many years; she ended up falling ill and reassessing her lifestyle, facing up to truths that she had never wanted to. She describes it like this; “I know the reasons that pushed me to adopt an extreme diet, and they are honourable reasons, you could even say noble. They are reasons like justice, compassion and a desperate and overwhelming desire to fix the world. I wanted to protect the vulnerable, the voiceless. I wanted to feed the hungry. I wanted to at least avoid participating in the horror of industrialized livestock farming”.

She takes a rigorous tour through the thesis at the heart of her book that she calls adult thought, which is to accept that death is everywhere, that death is part of life and makes life possible. “…That was the last time I entered the vegan forums. I realised that if someone was not aware of the nature of life with its cycles of minerals and its carbon exchanges, its equilibrium points based on the ancient cycle of producers, consumers and decomposers, they could not guide me, or take any useful decision about a sustainable human culture. By moving away from adult knowledge, from the understanding that death is a part of the sustenance of all creatures, these people could never calm the emotional and spiritual thirst I felt, precisely because I had accepted that knowledge. Maybe in the end this book is just an attempt to calm that pain.”

“I wanted to believe that my life – my physical existence- was possible without killing, without death. But it isn’t possible. There can be no life without death”.

She remembers how she awoke to the realisation of this truth, and she observed how her ethical anguish was no use to her vegetable garden. “There was no plant with the capacity to fix nitrogen that could compensate for all the nutrients that it extracted from the soil. The earth wanted manure. Even worse, I wanted the unthinkable: blood and bones. My garden wanted to eat animals, even though I did not want to. And so I came to another crossroads in my pilgrimage. I could buy a box of NPK fertilizer, perfectly balanced and ecological, or I could make friends with a farmer. The box was tempting, because it would allow me to lie. Or rather, to not know what I already knew. I read the label of the ingredients. Animal blood meal, animal bone meal, dead animals, dried and ground up. I tried to explain to a horrified vegan friend of mine that plants also need to eat. You have to replace what you take out of the ground. The only alternatives are fossil fuels or animal products … but my friend could not understand it, and he left in horror…”

“I wish I could go back in time and talk to myself ten years ago. The day will come when you will have a flock of pigeons and you will scatter

Lierre Keith

their dung and bury their dead among the fruit bushes and apple trees. And you will cry as you do so, not only because you will feel sad, but also because it is a sacred act and because it is the right thing to do. You have closed the circle and that will open your heart. You will also have chickens and ducks, and speckled hens. You will eat the fruit, eggs and meat. They will accept you, they will approach you for help and caresses, and you will love them. And all of you will eat; you, the birds, the fruit, the humans and the earth, and you will be eaten. As burials in the sky are forbidden, in your will you will write: scatter my ashes when it is my turn, so that they can feed the fruit bushes and the apple trees.”

“When you take a life to eat or to use it for the sake of your own survival, you become responsible for the survival and dignity of that other community.” The animist ethic accepts that every living being depends on others, that life itself is a chain of mutual dependence. Life and death are the same moment: for some to live, others must die.

“The Seneca tribe, for example, has a four-day thanksgiving ceremony, during which all that exists in the world is named and honoured. Around the planet and throughout history, we find numerous examples of cultures that face the human project of life with humility and respect for the lives on which we depend. But that attitude is only possible if we accept death. Apart from the destructive nature of a farmed diet, all attempts to exclude us emotionally, physically or spiritually from the processes of life on the planet will lead us to a culture based on ignorance, denial and, given our human capacity for destruction, domination. In order to do things right, we must face the truth about our existence.”

She also suggests that it is possible that traditional foods, traditionally recognised as essential, have been demonized by our culture; foods that provide us with essential fatty acids and essential amino acids that the body cannot synthesize. She rejects the idea that it is bad to consume lipids and fats, and talks about how children need cholesterol and saturated fats for their development, how without fats our neurotransmitters lose the ability to transmit, how zinc is a mineral that is very difficult to find and that egg yolks and red meat are the best sources of zinc …

Thank you for your book, Lierre. We can only teach from our own experience. The lines that link pain and beauty are so strange.

Excellent commentary on this important book, Lierre’s work really solidified my thoughts and feelings regarding Vegetarianism. Humans are facultative Carnivores and we should honor our marvelous, evolutionary past with reverence.